The 98-year-old coach leads his teams to the statue honoring Tommie Smith and John Carlos

By Urla Hill | October 23, 2018

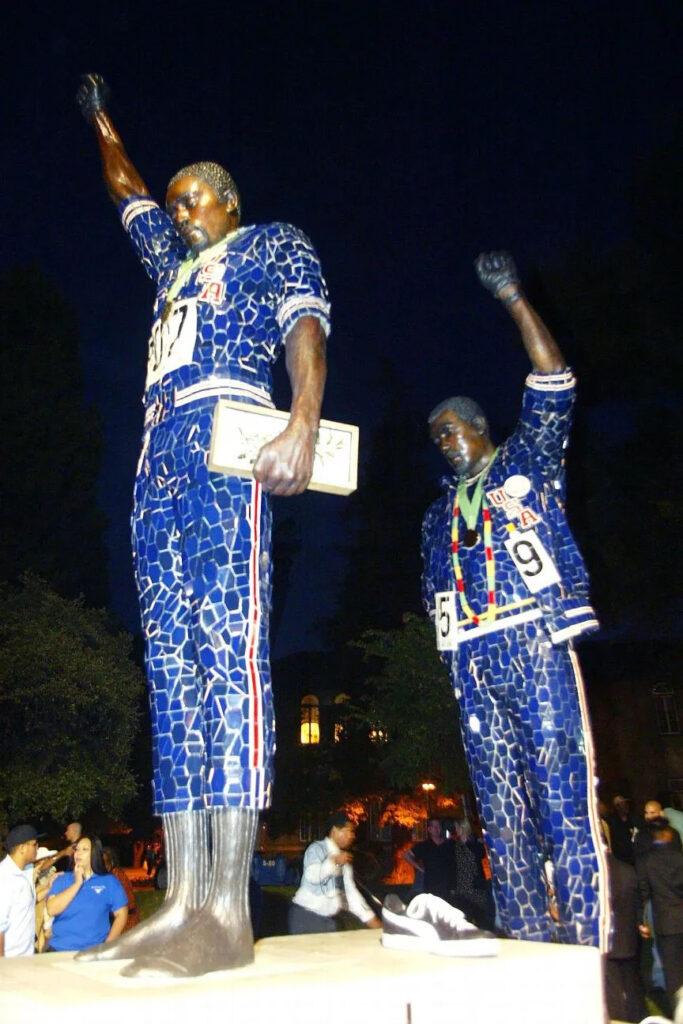

San Jose State University coach Yoshihiro Uchida takes his judo teams on an annual pilgrimage across campus, from the building named in his honor to the 23-foot sculpture depicting sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the winners’ podium at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City on Oct. 16, 1968.

Although the moment is billed as a “Black Power” protest, the medalists bore symbols of empathy on the dais: Carlos’ tracksuit was unzipped in a show of solidarity with blue-collar workers, and the beads he wore represented those who had been hanged, killed, lynched and tarred. Smith held an olive branch as an emblem of peace and wore a black scarf for black pride. Both wore black socks, but neither wore shoes.

Uchida, who turned 98 in April, remains impressed that Carlos and Smith “had the courage to speak out against discrimination.”

“I think it is important for the students to view the statue because [Smith and Carlos] are Americans, not just black people,” said Uchida, who came to San Jose State as a student in 1940 and started coaching judo in 1941. “When they went on the world’s stage, they represented all of us as Americans.”

“In judo, you help the weak. If you see someone in trouble, you stand up for them.”

After the 1968 Games, Smith and Carlos — the 200-meter gold and bronze medalists, respectively — faced backlash. After swift suspensions — International Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage argued that the sprinters “violated one of the basic principles of the Olympic Games: that politics play no part whatsoever in them” — Smith and Carlos’ memory languished for decades.

“I thought what Smith and Carlos did took a lot of guts,” Uchida said. “I had seen how blacks in this country were treated. I knew how difficult it was for blacks to get access to apartments, and then, even after graduation from school, many times there were no jobs available.”

As an American of Japanese ancestry, Uchida understands the fear, hatred and racism directed at Smith and Carlos.

Uchida was a student on campus when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, but he was drafted before President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, the directive ordering the removal of the Japanese from the West Coast to concentration camps in the U.S. interior in February 1942. Uchida’s family was first sent to the War Relocation Authority’s camp in Poston, Arizona, that spring.

The Uchidas, along with other Issei (first generation), Nisei (U.S.-born, second generation), Sansei (U.S.-born, third generation) and Kibei (born in the U.S. but educated in Japan), became known as “no-no boys” because of their responses to questions 27 (“Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”) and 28 (“Will you swear unqualified allegiances to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or other foreign government, power or organization?”) on a survey that internees were required to take.

During the early months of his family’s internment, Uchida was transferred from Fort MacArthur Air Force Base in San Pedro, California, to Camp Robinson in Little Rock, Arkansas.

“We rode across the country by train with the shades pulled down,” said Uchida, who, except for a trip to Japan as a baby during the 1920s, had never left California. “One of my friends needed to use the restroom once we arrived at the train station in Arkansas, but we didn’t know which one to use. We had never seen signs that said ‘colored.’

“Once we started walking toward the ‘colored’ sign, someone told us, ‘No, you use that over there,’ pointing to the sign that said ‘white.’ ”

Having grown up on his father’s farm in rural Orange County, Uchida had yet to experience the type of discrimination on display in the South. He does, however, remember his Mexican classmates being sent to a new elementary school during the late 1920s. (The 1947 case Mendez v. Westminster would set the precedent for Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.)

After World War II, Uchida and the many other Japanese citizens who returned to the West Coast would experience housing and job discrimination. He and his young family eventually settled on the farm of Sam Della Maggiore, who once coached Uchida in wrestling at San Jose State.

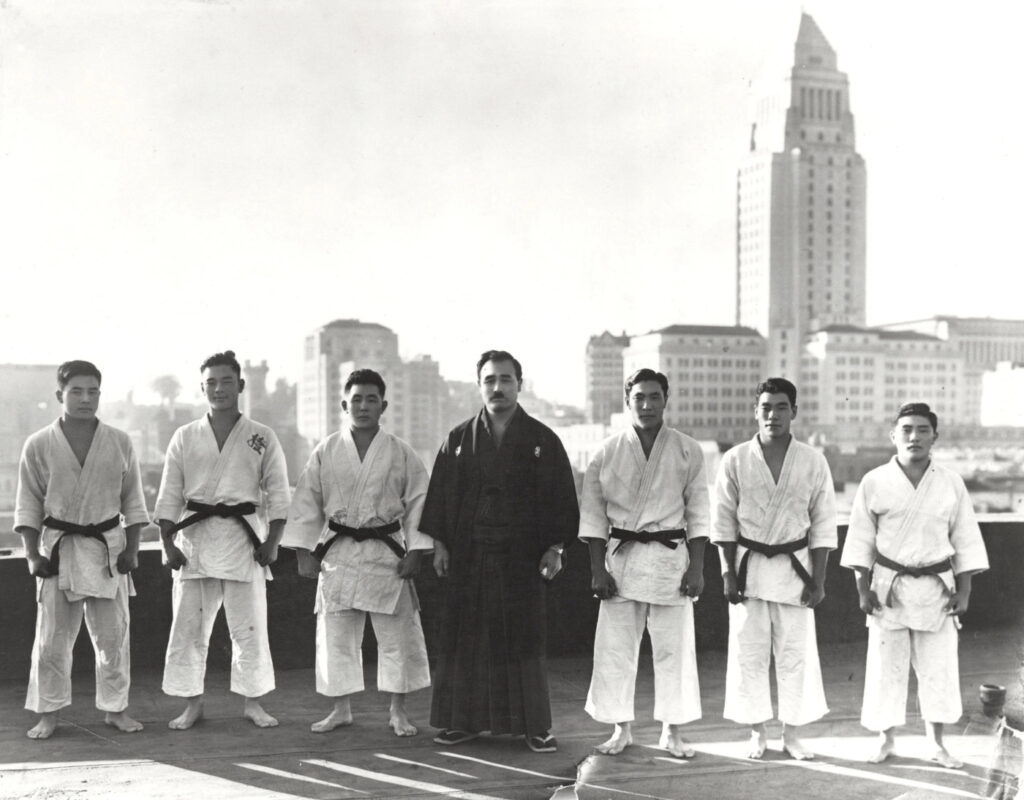

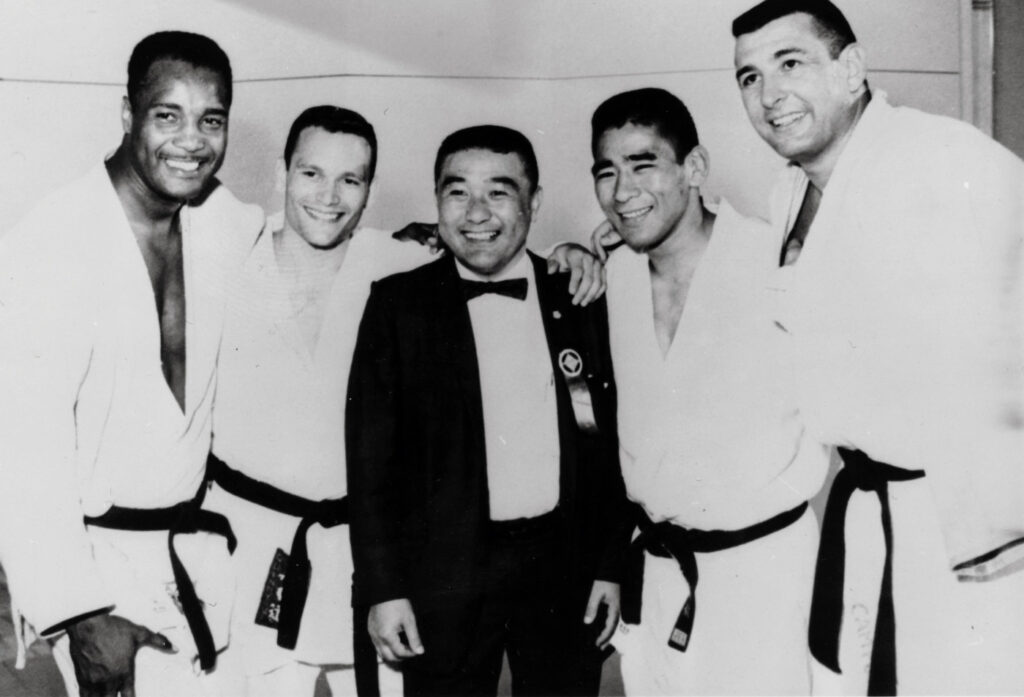

Uchida started coaching judo for the college’s police academy soon after his arrival from Garden Grove, California, in 1940. His Spartans have since amassed 51 of the 56 National Collegiate Judo Association (NCJA) titles since the league’s inception in 1962, and he became the first U.S. Olympic judo coach in 1964.

The actions of Uchida’s brothers and many other Japanese-Americans better enabled Uchida’s understanding of Harry Edwards’ Olympic Project for Human Rights. Edwards, a 1964 graduate of San Jose State who returned there as a lecturer during the fall of 1967, had called for a boycott of the Spartans’ 1967 football season opener against the University of Texas-El Paso.

“Something like that had never happened before,” Uchida said. “It was a first locally and nationally, and attracted the attention of [then-Gov.] Ronald Reagan.”

After the success of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, Edwards would define a list of demands for the U.S. Olympic Committee, including the restoration of Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight boxing title, the hiring of more African-American coaches, the removal of South Africa and Rhodesia from the games and the removal of Brundage at the IOC.

Smith and Carlos’ standing at SJSU would eventually change, too, thanks to the curiosity of business major Erik Grotz. Once Grotz discovered the duo’s connection to the university, he questioned why nothing had been placed on campus to honor them.

In October 2002, 34 years after the medalists’ stand on the dais, Alfonso De Alba, executive director of SJSU Associated Students, announced the university’s intention to begin a fundraising campaign to build the statues. And in 2005, Portuguese political artist Rigo 23 unveiled the 23-foot statues of Smith and Carlos standing shoeless, each with a bowed head and a single, black-gloved fist.

“We saw the statue and Coach Uchida started explaining the story,” Colton Brown, who served as team captain en route to three NCJA titles, said of his memory in 2010. “We even took a picture in front of it. After that, my dad bought a picture of it, framed it and put it in our house.”

Brown, who is now training in Boston in hopes of making the 2020 Olympic team, said Uchida’s speech that day gave him a good sense of his character. “One thing that he said was, ‘I could never get myself to hate a group of people after what happened to me as a Japanese-American.’ I really respect that.”

When Edwards and SJSU announced the Institute for the Study of Sport, Society and Social Change in 2017, Uchida required team members to attend the panel that featured athletic greats such as former Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown and former Los Angeles Lakers center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

“It was mandatory,” Brown said.

Uchida’s experience on campus has added to his coaching philosophy.

“In judo, you help the weak,” Uchida said. “Our philosophy is to help people stay away from trouble if you can. If you see someone in trouble, you stand up for them.”

What some might deem as most remarkable about Uchida is that he is legally blind but continues to coach.

Sophomore Laurel Zemke, who manages and competes for the team, visited SJSU after the Spartans traveled to Enumclaw High School in Washington state for a judo jamboree that was sponsored by a former Spartan. After meeting Uchida, she and her mother traveled to San Jose. She said it was the best decision she ever made.

“It’s hard to form bad habits because he is always looking,” Zemke said.

SJSU graduate and four-time NCJA champion Marti Malloy agrees.

“I don’t know how he does it, but he does,” said Malloy, a bronze medalist at the Olympic Games in 2012. “Even if it’s a fraction of a wrong move. I don’t know, is it his instinct?

“He can’t see clearly, but he still sees judo.”

Uchida laughed at the comment and said, “Well, I can tell if someone is doing something wrong because of the long list of players I have watched over the years.”

Although Malloy now works as a social media manager an hour north of San Jose, she makes an effort each day to get to practice by 6 p.m.

“Coach has a rough exterior, but he recently suffered a terrible loss” with the death of his wife, Mae, in May, Malloy said. “I just want to try to make him laugh.

“Sometimes I know I am not going to get to practice on time, but I go anyway, just to see him. I like the fact that he was my coach, my mentor, and now my friend.”

Uchida has been recognized by the San Jose State Spartan Hall of Fame, the San Jose Sports Authority’s Hall of Fame and the Multi-Ethnic Sports Hall of Fame. In 2008, the USA Judo Hall of Fame inducted Uchida and Spartan Mike Swain, a four-time Olympian and former world champion, onto its initial team.

In 2020, Tokyo will host the Summer Olympics for the first time since 1964.

“I want to go,” said Uchida, who will be 100 years old in 2020. “This will only be the second time the games will be held in Tokyo.”

In the meantime, Uchida will continue to teach important lessons through judo, even comparing the quiet stance taken by Smith and Carlos to the judokan way.

“Ju is gentle, and do is the building of character in the individual,” he said. “The word itself means ‘a road.’ … And all these — being humble, not looking for a fight, pushing forward, persistence — are included on that road and gives that person a certain confidence as he moves through life.”

Urla Hill, a two-time San Jose State University graduate, spends most of her free time chronicling the Spartans’ athletic program between 1920 and 1972.

https://andscape.com/features/san-jose-states-yoshihiro-uchida-teaches-more-than-just-judo/